Whitworth Rifle

The Whitworth rifle was, arguably, the first long-range sniper rifle in military history. This innovative rifle was designed by Sir Joseph Whitworth, a famed British engineer and inventor. In an effort to overcome the weaknesses of the British infantry rifle (the Pattern 1853 Enfield), Whitworth began working on his new design in 1854.

Up to that time, a rifle barrel simply had a grooved surface that would actually slightly cut into the bullet to be able to grip the round and put spin on it. This friction naturally slowed the velocity of a shot fired from such a barrel.

It was also known that tighter rifling (the Enfield's rifling made one turn in seventy-eight inches) could produce greater accuracy; but at the same time, it increased friction, which caused the bullet to slow, which reduced range.

Whitworth set out to design a rifle that would reduce friction while being rifled much more tightly than the Enfield. He believed this would produce a weapon that would be much more accurate, and would have a greater range. Man, was he ever right...

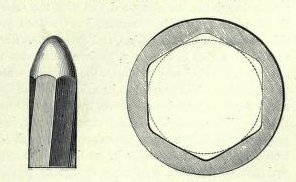

In order to achieve this goal, Whitworth had to re-imagine how to rifle a gun-barrel. His solution was to create a hexagonal barrel and and a hexagonal bullet to match (right). This allowed the bullet to fit snugly into a smooth, un-grooved barrel, greatly reducing friction.

At the same time, the hexagonal shape of the barrel was twisted, or rifled, at a rate of one turn in twenty inches. This was more than three times tighter than the rifling of the Enfield rifle.

Thanks to the fact that the rifling in no way cut into the bullet, the Whitworth rifle was able to fire its rounds at higher velocity than the Enfield rifle, despite having the much tighter rifling. The combination of tight rifling and high velocity made the Whitworth the most accurate rifle of its day.

Outstanding Accuracy

In 1857, the Whitworth rifle received its first head to head trial against the Enfield, in the presence of the British Minister of War. At this trial, the Whitworth outperformed the Enfield at a rate of three to one. Following are the comparative groupings of the two weapons at various distances in this trial...

Range: 500 Yards

Whitworth: 4.44 inches

Enfield: 26.88 inches

Range: 800 Yards

Whitworth: 12 inches

Enfield: 49.32 inches

Range: 1100 Yards

Whitworth: 28.92 Inches

Enfield: 96.48 inches

Range: 1400 Yards

Whitworth: 55.44 inches

Enfield: ---No hits---

Range: 1800 Yards (Just over one mile.)

Whitworth: 139.44 inches

Enfield: ---Not fired---

At just over a mile, the Whitworth rifle's group was almost twelve feet, this may not seem extremely accurate. However, we must consider the fact that the shooter would probably be firing on a group of officers or artillery men. In which case, being able to consistently hit a twelve foot target would at least cause great disorder, if it did not prove deadly.

The Queen of England even used the Whitworth rifle with good results:

"The first meeting of the British National Rifle Association was held at Wimbledon in 1860. The first shot was fired by Queen Victoria, from a Whitworth rifle on a machine rest, at 400 yards, and struck the bull's-eye at 1 1/4 inches from its centre."

Before you get too impressed, you should probably know what a "machine rest" was. Basically, it allowed the rifle to be aimed and secured in position for the Queen, so that (by pulling a string that was fastened to the trigger) she could fire the gun while standing well clear.

Despite all these promising signs, the Whitworth was never adopted by the British government. There were two main reasons for this. First, the unique barrel design was more easily fouled, meaning it needed more frequent cleaning than a traditional barrel; and secondly, the Whitworth cost about four times as much to manufacture as the Enfield rifle.

While it never saw action in the British Army, the Whitworth rifle got to prove its usefulness on the battlefield on the other side of the Atlantic...

Confederate Snipers

The Confederate government, purchased a limited number of Whitworth rifles during the Civil War. These weapons were given to the very best marksmen in the Confederate Army. This select group of men were referred to as Whitworth Sharpshooters, thus were born the first modern sniper units.

Most of the Whitworth rifles used by the Confederates were equipped with open sights. The front sight was usually adjustable for distance, and in some instances was also adjustable for windage. A small number had telescopic sights which, unlike modern top-mounted rifle scopes, were mounted on the left side of the rifle.

On a side note, the Whitworth was a light gun, and therefore had very hard kick. Because of this, those sharpshooters who used a scope often left the battlefield with a black eye, thanks to the blows they received from their scope when the rifle recoiled.

These men were often sent out to find vantage points from which they could harass and eliminate Union artillery crews. They did not limit themselves to artillery targets, however. When the opportunity presented itself, these early snipers would draw a bead on enemy officers as well.

On September 20, 1863, at the Battle of Chickamauga, an unknown Confederate sniper shot Union General William Haines Lytle off his horse while the General was leading a counterattack. When the General's body was identified, the Confederates placed an honor guard on the body until it could be recovered.

The most famous act of sniping during the Civil War also involved a Whitworth rifle. It took place on May 9, 1864, at the Battle of Spotsylvania Court House. Accounts vary as to the distance from which the shot was taken, with the range being put anywhere from 500 to 1000 yards. It is likely that it was closer to 500 than 1000, but we will never know for sure.

Union General John Sedgwick was directing the placement of his artillery in preparation for the coming battle when his position came under fire from a Confederate sniper. The unique shape of the Whitworth bullets caused them to make a very distinctive whistling sound when they passed through the air; a sound that was, by then, feared in the Union ranks. Following is an account of what happened next, from Sedgwick's Chief-of-Staff:

"As the bullets whistled by, some of the men dodged. The general said laughingly, 'What! what! men, dodging this way for single bullets! What will you do when they open fire along the whole line? I am ashamed of you. They couldn't hit an elephant at this distance.' A few seconds after, a man who had been separated from his regiment passed directly in front of the general, and at the same moment a sharp-shooter's bullet passed with a long shrill whistle very close, and the soldier, who was then just in front of the general, dodged to the ground. The general touched him gently with his foot, and said, 'Why, my man, I am ashamed of you, dodging that way,' and repeated the remark, 'They couldn't hit an elephant at this distance.' The man rose and saluted and said good-naturedly, 'General, I dodged a shell once, and if I hadn't, it would have taken my head off. I believe in dodging.' The general laughed and replied, 'All right, my man; go to your place.'

For a third time the same shrill whistle, closing with a dull, heavy stroke, interrupted our talk; when, as I was about to resume, the general's face turned slowly to me, the blood spurting from his left cheek under the eye in a steady stream. He fell in my direction; I was so close to him that my effort to support him failed, and I fell with him."

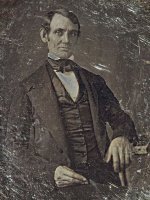

Thus, General Sedgwick became the highest ranking Union officer to die in battle (above). When General Ulysses S. Grant received the news, he was so shocked that, in total disbelief, he repeatedly asked those around him, "Is he really dead?"

Although five different Confederate snipers claimed to have been responsible, it has never been confirmed who took the most famous shot ever fired from a Whitworth rifle.

American Civil War Story - Home

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.