LaFayette Baker

LaFayette Baker was one of the leading American Civil War spies who served the Union government. His story is a fascinating one, which includes narrow escapes, treachery, accusations, disgrace, and conspiracy theories...

Little is known about LaFayette Baker's early years (right), but it is known that he headed to California to try his luck during the gold rush. He did not find success as a prospector; so he turned to other pursuits. He joined the 1856 San Francisco vigilance committee which took control of the city government in an effort to put a stop to crime and corruption. It is believed that Baker took part in a number of lynchings during this period, and was asked to take a position on the San Francisco Police force after the committee was dissolved.

Baker remained in California until 1861, but with news of the burgeoning rebellion, he rushed back east to see if he could secure some position with the Union Army. With this in mind, he somehow received an interview with the Union Commander at that time, General Winfield Scott.

LaFayette Baker apparently succeeded in making a good impression on the old General, because he was asked to undertake an espionage mission into Confederate territory. Baker asked for time to take care of some personal matters before any final decisions were made. General Scott agreed, and Baker went to New York for a short time before returning to Washington...

Union Spy Chief

The latter part of June, I was again in Washington, and had repeated interviews with the General. The result was, a definite arrangement for a journey toward Richmond, if not into the rebel capital. Directions in detail were given me respecting the difficult service I was expected to perform.

Taking from his vest pocket ten double eagles of coin, General Scott handed them to me, expressing the warmest hopes of my success in the excursion to "Dixie."

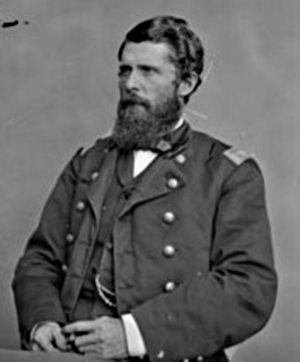

At this point, LaFayette Baker (left) adopted the alias Sam Munson and attempted to begin his expedition. Unfortunately, he was almost immediately arrested as a spy... ...by Union troops around Alexandria, Virginia! Upon being sent back to Washington for trial, Baker was freed by General Scott and told to "Try again."

Following another failed attempt, Baker finally succeeded in escaping his own men and made his way into Confederate territory.

It seems "Mr. Munson" must have seemed very disreputable, because the Confederate troops (just like their Union counterparts) soon arrested him under suspicion of being a spy. He was then interrogated by General Beauregard at Manassas Junction (the future site of the First Battle of Bull Run). Baker was then taken to Richmond, where he claims he was interrogated by Confederate President Jefferson Davis. Baker says he then convinced all questioners of his innocence and obtained a pass to travel to Fredricksburg, Virginia.

Having gathered all the military information he could, Baker then ignored his pass and headed straight for the Potomac River and safety. After a couple of close scrapes, including escaping temporary capture, he made his way to a small tributary of the Potomac, where he met some Dutchmen from the Confederate Army. He represented himself as a local landowner who was out to see how the soldiers were doing. Then he asked if they might spare him something to eat:

In a few minutes they set before me a supper simply of fish, cooked in their primitive style, and yet no luxury was ever so grateful to the taste. After it was finished, I asked for a pipe, and began to puff away, entirely at home; but all the while revolving in my mind the chances and expedients for a final parting with my Dutch friends. Finally, my eye fell upon a small boat lying in the bushes below; and the conviction followed the discovery, that it was my only hope of crossing the Potomac. Learning that the fishermen owned it, I said to them:

"I want to buy that boat. What will you take for it?"

"I no sells dat poat," replied one.

"I'll give you twenty dollars for it, in gold."

"It's worth more as that to us. The Yankees ish breaking up all poats on the Potomac."

There was an end to the prospect of a purchase; and a new plan must be devised.

---

LaFayette Baker then asked to stay with the two men for the night, and they reluctantly agreed. After waiting for them to fall soundly asleep, he made a break for it...

---

... I hastened to the bank. To my great disappointment, there were no oars in the boat. Upon making search among the willows, I found a short one, partially decayed. Noiselessly as possible I launched the frail bark, fearing each sound on the sand or in the water would bring my Dutch friends down the bank. In a few moments, which suspense made oppressively long, I floated away into the stream, at this point, not over thirty feet in width. Taking the middle of the current, I pulled off my coat, and began to row for life. The tide favored me, and I was congratulating myself upon the prospect of an unmolested voyage, when a shout drew my attention to the vigilant Dutchman, whose gesticulations could not be misunderstood. He called loudly to his bedfellow: "Meyer! Meyer! the poat ish gone! the poat ish gone!"

He seized his musket and made for the bank, not more than a dozen feet from me, shouting:

"Come pack here! Come pack mit that poat!"

My only answer was a more vigorous use of the oar

Placing my right hand upon the pistol, and watching the soldier, I propelled the boat with my left.

"Come pack!" he continued, following me along the bank. He then paused, leveled his musket, and was about to fire. I did not want to kill "mine host," but the law of self-defense again demanded a sacrifice. With quick and sudden aim, I fired—with a cry of distress, he staggered and fell lifeless beside his musket. His comrade was running down the hill, when, seeing what had happened, he turned back to the tent. He soon returned with a double-barreled shot gun, and stole along cautiously, through the bushes, till within forty yards of the boat, and then fired. The shot fell around me, in the water. Catching a glimpse of my enemy in the thicket, I discharged my revolver. He ran away, evidently unhurt. The reports had given the alarm, and several soldiers soon came in sight. An instant later, a bullet whistled over my shoulder. I had reached the decisive moments of my last effort to get out of "Dixie." Again getting sight of the Dutchman in the bushes, I once more took deliberate aim and fired. He threw up one arm, gave a yell, and fell to the ground. In a moment he rose again, and, groaning, staggered away. Then two or three shots saluted me unceremoniously, striking and splintering the side of the boat. I was now at the mouth of the creek, and rapidly left the shore behind me. A squad of soldiers, by this time, stood on the brow and at the base of the hill, firing their muskets. The chug of the bullets in the water reminded me that my transit to loyal soil was not yet certain. Both hands were laid to the oar, and, striking the broad current of the Potomac, which was here four miles wide, I rapidly receded from musket range. A high wind swept the waters, and, while rounding a bluff, a sudden gust carried away my hat, and lifted my coat lying in the bow of the boat, dropping it into the river. But it was no time to look backward to those articles of apparel, floating between me and my foes, whose bullets still came unpleasantly near. Their shots continued until they fell far in the wake of my boat. The sun had risen above the horizon, warm and bright, while, for two hours and a half, I worked with a single oar, and, aided by the drifting tide, approached the Maryland shore.

Upon Baker's safe return to Washington General Scott made him a Captain and head of his intelligence department. When news spread of his heroic exploits, Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton recruited Baker to be the head of the Union Intelligence Service. Stanton then gave him a job as head of the National Detective Police.

In this capacity, Baker operated essentially as the head of a secret police, seeking out and punishing any activity he deemed corrupt or rebellious.

He developed a reputation for arresting and punishing suspects, "without warrant, or the semblance of law or justice."

Baker once unearthed widespread corruption within the Treasury Department. While there was undoubted criminal activity, some felt that the only reason it came to light was because Baker didn't get a cut. One Treasury Department official commented, "Baker became a law unto himself. He instituted a veritable Reign of Terror. He always lived in the first hotels [and] had an abundance of money."

Eventually, LaFayette Baker had a disagreement with his boss, Secretary Stanton, and was demoted to a lower investigative position. Some believe the disagreement stemmed from Stanton's belief that Baker was tapping the telegraph lines leading to Stanton's office. Whatever the cause, Baker was sent off to New York as punishment.

That all changed when President Lincoln was assassinated. Secretary Stanton immediately reinstated Baker and asked that he use his network of detectives and informants to track down John Wilkes Booth. Within two days, Baker had the names of the conspirators and had made four arrests. Within two weeks, his men had found and killed the assassin himself. For this reason, Baker received a large part of the $100,000 reward on offer for Booth's capture.

Baker was also promoted to Brigadier General as a reward for his work in bringing the conspirators to justice. However, Baker's involvement did not end there...

Lincoln Assassination Conspiracy Theories

In 1866, President Johnson removed LaFayette Baker from office, because he was spying on the White House. Baker soon published a book in which he admitted to spying on the President, but claimed he was doing so under orders from Secretary Stanton.

The most interesting thing to come from his book, however, was the fact that his men had taken a diary (which Baker had then given to Secretary Stanton) from the body of John Wilkes Booth. Somehow, this diary was not part of the evidence presented during the trials of Booth's supposed fellow conspirators. Since there was some concern about the validity of those trials, especially the execution of Mary Surratt, the possible suppression of evidence in the case was a big deal. The War Department soon produced the diary which did not seem to contain anything too important, but Baker claimed that pages had been removed from the diary since he had handed it over.

In 1868, LaFayette Baker died. The official cause of death was meningitis. This is where we find the beginning of many conspiracy theories surrounding the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. In the 1960s, Professor Ray Neff, from Indiana State University, performed tests on Baker's remains, and claimed that his actual cause of death was arsenic poisoning.

This claim, combined with Baker's assertion that pages had been removed from the Booth diary, lead many to believe that Secretary Stanton was trying to cover up some involvement in Lincoln's assassination. One problem, however, is that while giving testimony on the matter before the U.S. House of Representatives Judiciary Committee, Baker admitted that he did not know whether or not pages had been removed from the diary. Combining this admission with the fact that he was caught in a couple lies while testifying before this committee, his claims seem somewhat baseless.

At one point in his testimony, Baker tried to implicate President Johnson as a Confederate spy who might have played a part in Lincoln's assassination. He even claimed to have access to letters sent between Johnson and Confederate President Davis, that would prove his allegations. However, Baker was never able to produce the alleged letters, and after investigating the claims, Congressman Benjamin F. Butler of Massachusetts, a known enemy of President Johnson admitted, "...there was no reliable evidence at all to convince a prudent and responsible man that there was any ground for the suspicions entertained against Johnson."

While LaFayette Baker's claims seem questionable and even downright ludicrous, they raise just enough doubt to spawn many, far-reaching, conspiracy theories. However, there is not enough room to relate them here, so they will have to wait for another page...

American Civil War Story - Home

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.