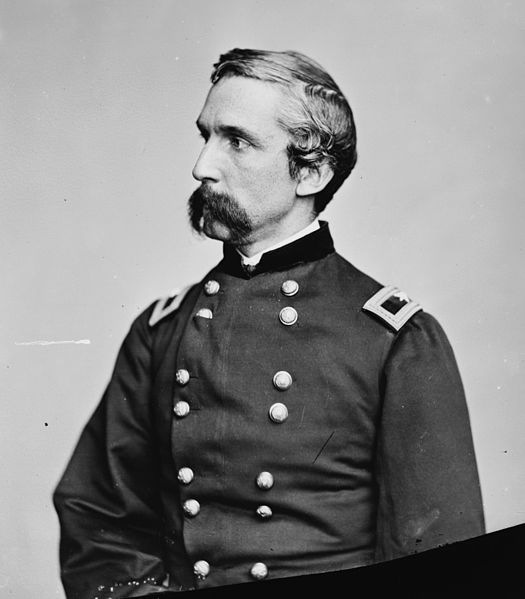

Joshua Chamberlain

At the outbreak of the American Civil War, Joshua Chamberlain (right) was eager to serve his country, but his employer was not so eager to see him go...

Chamberlain was a professor at Bowdoin College and was extremely well educated. He was fluent in nine languages. When he expressed his desire to serve, the administration at Bowdoin prevented him from doing so. He did not let this stop him. In 1862, he asked for and received a leave of absence to travel to Europe to study languages. Instead, he immediately volunteered his services and secured a position as Lieutenant Colonel of 20th Regiment of Maine Volunteer Infantry.

During his time in the Union Army, Joshua Chamberlain would go from inexperienced officer to Major General. He would become a hero for his bravery in battle, and for returning to lead his men after reportedly dying. He would even earn the appreciation of his enemies. All in all, he was a true American Civil War hero.

One of Chamberlain's first combat experiences was at the bloody Battle of Fredericksburg, in December of 1862. After many assaults had already been repulsed by the Confederates, Chamberlain and his regiment were sent out as well. Unfortunately, they were forced to spend the night on the battlefield and were forced to extreme measures in an effort to stay warm:

"It was a cold night. Bitter, raw north winds swept the stark slopes. The men, heated by their energetic and exciting work, felt keenly the chilling change. Many of them had neither overcoat nor blanket, having left them with the discarded knapsacks. They roamed about to find some garment not needed by the dead. Mounted officers all lacked outer covering. This had gone back with the horses, strapped to the saddles. So we joined the uncanny quest. Necessity compels strange uses. For myself it seemed best to bestow my body between two dead men among the many left there by earlier assaults, and to draw another crosswise for a pillow out of the trampled, blood-soaked sod, pulling the flap of his coat over my face to fend off the chilling winds..."

He goes on to talk about creeping across the battlefield in the dark, trying to tend to miserable, wounded men that had to lie exposed through the night. He left Fredericksburg largely without incident, and would not truly begin to make a name for himself until the next year.

Chamberlain is most well remembered today for his fearless defense of Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg. This story has become the focus of many modern depictions of the Battle of Gettysburg, including the outstanding novel The Killer Angels. During the second day of the battle, Chamberlain was sent to defend the left flank of the Union line at Little Round Top. There he and his men repulsed assault after assault from Confederates under General John B. Hood. Eventually, with his men running low on ammunition, Chamberlain ordered a desperate bayonet charge which dislodged Hood's men and secured the Union flank. Chamberlain was eventually awarded the Medal of Honor for his leadership that day. He also suffered two wounds during the defense of Little Round Top...

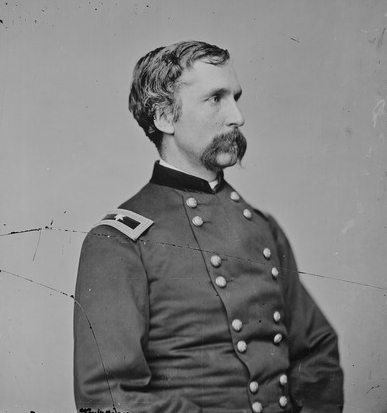

Battle Wounds

Joshua Chamberlain (left) was a resilient officer who fought despite being wounded often. The fact that he was wounded six times and had six horses shot from beneath him, is a testament to his bravery and the fact that he never shrank from enemy fire.

As was mentioned, he received two wounds at the Battle of Gettysburg. Both of these wounds were fairly minor. In the one instance, a bullet struck his scabbard and was deflected away, leaving him with only a sore leg. His second wound was in the foot and was the result of either a spent round or a fragment of shrapnel. While these wounds were not serious enough to keep him from his command, he was forced to take time off to recover from a severe illness.

He was not able to return to duty until April of 1864. Unfortunately, the minor nature of these wounds would not be a good predictor of the severity of Chamberlain's future wounds.

In June of 1864, Chamberlain took part in the Siege of Petersburg. On June 18, he and his men were engaged in fierce fighting in the area of Rives' Salient, when Chamberlain suffered his most severe wound. This wound nearly proved fatal. He was shot in the hip, and the bullet traversed his pelvic region, damaging his bladder and urinary tract. At the time that he received this wound, Chamberlain's men were in great disarray and were about to retreat. To prevent this, he drew his sword and used it to prop himself up so that he could continue to give orders. He soon fainted from blood loss and fell to the ground unconscious.

The first Army surgeon that saw him declared the wound fatal. However, two other surgeons preformed a somewhat experimental surgery to extract the bullet and repair his damaged bladder and urinary tract. It was still believed that Chamberlain would die, and his obituary even appeared in some Maine newspapers. General Ulysses S. Grant was persuaded to give Chamberlain a battlefield promotion to Brigadier General, to honor his courage in death, but...

The new General, Joshua Chamberlain, had other ideas. He made a valiant recovery and returned to command that very November.

Chamberlain suffered another interesting wound less than two weeks before Lee's surrender. During a skirmish along Quaker Road, he was struck by a shot on the left side of his chest. Luckily for him, the bullet had already passed through his horse's neck, and it also struck some items in his left breast pocket. These combined factors caused the bullet to be turned slightly and it travel under his skin, along a rib, and came out at the rear of his armpit. He was briefly knocked unconscious.

To everyone who saw it, it looked for all the world like he had been shot through the chest, and probably through the heart. Once more, it was believed that General Joshua Chamberlain was dead. This fact was even reported via telegram in New York. But once more, Chamberlain survived. He later wrote that his survival provoked a great reaction from men on both sides who had seen him get hit. "I was astonished at the greeting of cheers which marked my course. Strangest of all was that when I emerged to the sight of the enemy, they also took up the cheering. I hardly knew what world I was in."

The Gracious Victor

After Lee's surrender at Appomattox Court House, Virginia (above), on April 9, 1865, General Joshua Chamberlain was selected to oversee the formal parade and surrender of the Confederate Infantry on April 12. As the Confederates, under General John Brown Gordon, marched forward to relinquish their arms and furl their flags, Chamberlain gave an order that would give the terrible war a fitting end. He ordered his men to stand to attention and "carry arms," as a salute to the Confederate soldiers. General Gordon was deeply moved, and ordered his men to return the honor in kind. Here is Chamberlain's description of the scene:

"The momentous meaning of this occasion impressed me deeply. I resolved to mark it by some token of recognition, which could be no other than a salute of arms. Well aware of the responsibility assumed, and of the criticisms that would follow, as the sequel proved, nothing of that kind could move me in the least. The act could be defended, if needful, by the suggestion that such a salute was not to the cause for which the flag of the Confederacy stood, but to its going down before the flag of the Union. My main reason, however, was one for which I sought no authority nor asked forgiveness. Before us in proud humiliation stood the embodiment of manhood: men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now, thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond;—was not such manhood to be welcomed back into a Union so tested and assured?

Instructions had been given; and when the head of each division column comes opposite our group, our bugle sounds the signal and instantly our whole line from right to left, regiment by regiment in succession, gives the soldier's salutation, from the "order arms" to the old "carry"—the marching salute. Gordon at the head of the column, riding with heavy spirit and downcast face, catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual,—honor answering honor. On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word nor whisper of vain-glorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!

As each successive division masks our own, it halts, the men face inward towards us across the road, twelve feet away; then carefully "dress" their line, each captain taking pains for the good appearance of his company, worn and half starved as they were. The field and staff take their positions in the intervals of regiments; generals in rear of their commands. They fix bayonets, stack arms; then, hesitatingly, remove cartridge-boxes and lay them down. Lastly, — reluctantly, with agony of expression, — they tenderly fold their flags, battle-worn and torn, blood-stained, heart-holding colors, and lay them down; some frenziedly rushing from the ranks, kneeling over them, clinging to them, pressing them to their lips with burning tears. And only the Flag of the Union greets the sky! "

While there was some amount of disapproval throughout the north because of his actions, Chamberlain was remembered with appreciation by many southerners. Not least of which was General Gordon, who would later refer to Chamberlain as, "one of the knightliest soldiers of the Federal Army."

Joshua Chamberlain went on to serve as Governor of Maine, and as president of the school he ran away from, Bowdoin College. The old General passed away, largely due to complications from his Petersburg wound, on February 24, 1914. It was almost fifty years after he was said to have died from that very same wound.

American Civil War Story - Home

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.