History of Taps

The history of Taps is somewhat clouded by myth and legend, but the importance of this iconic bugle call cannot be argued. The twenty-four notes of Taps compose, arguably, the most recognizable and emotionally charged music ever played on a bugle. Although we usually associate Taps with military funerals (right), that was not always the case.

Originally, Taps was intended to signal lights out, but it was not long before it was co-opted as an important part of military funerals in America. According to most accounts of the history of Taps, soon after the tune was written in 1862, it was first used in a funeral ceremony:

"During the Peninsula Campaign in 1862, a soldier of Tidball's Battery A of the 2nd Artillery was buried at a time when the battery occupied an advanced position concealed in the woods. It was unsafe to fire the customary three volleys over the grave, on account of the proximity of the enemy, and it occurred to Capt. Tidball that the sounding of Taps would be the most appropriate ceremony that could be substituted."

Despite being widely used during military funerals for many years, Taps was not made an official part of the military funeral service until 1891.

So, we know what Taps is, and how it came to be used as a part of military funeral honors... ...but where does the tune itself come from? Good question! To find out, read on...

Legend of the Origin of Taps

Such a moving and iconic piece of music is bound to have a great story attached to it isn't it? Yes it is, but that doesn't necessarily mean that the story is true...

There is a common legend surrounding the history of Taps that has been around for years, and has taken on a new life in the internet age. It goes something like this...

In 1862, Union Captain Robert Ellicombe was hunkered down with his men near Harrison's Landing, Virginia. The Union army was being pressed by the Confederates after having been routed during the Seven Days Battles.

One night, Captain Ellicombe heard a wounded soldier moaning in the no-man's-land between the two armies. Risking his own life, the Captain moved out between the lines to carry the wounded man to safety.

When he was finally back behind his own lines, Captain Elliscombe discovered that the young soldier he had carried was actually a Confederate, and had died just as they reached the hospital tent.

Upon further inspection, the face of the Confederate soldier looked somewhat familiar. Suddenly, the Captain came to the shocking realization that the young man was his own son.

Consumed by grief, Captain Elliscombe asked to be able to bury his boy with military honors, but he was denied, because, his son was a Confederate. However, he was allowed to have a bugler to play as his son was lowered into his grave.

When asked what he would like the bugler to play, the Captain provided a piece of paper that his son had been carrying. On the paper was written a series of twenty-four notes. It is said that this haunting scene was the first time that Taps was ever played.

This story originated with Ripley's Believe it or Not, and seems to fall into the Not category. The largest flaw in the story is the fact that there is no record of a Captain Elliscombe having ever served in the Army of the Potomac. Unfortunately, this legend has obscured the true history of Taps and how it was originally written...

True History of Taps...

The true history of Taps is much less romantic, but there was one kernel of truth in the Captain Elliscombe story. Taps was, in fact, written at Harrison's Landing, after the Seven Days Battles, in 1862.

...but as we already know, it did not originate as a piece of funeral music. It originated as a call for lights out...

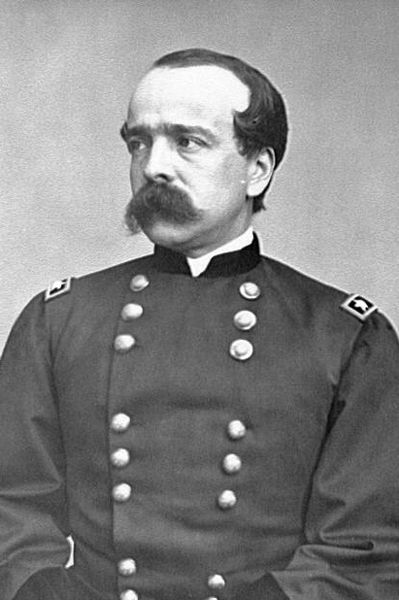

At that time, the call for lights out was a French tune called Extinguish Lights, but Union General Daniel Butterfield (left) felt this was too formal. Instead, he wanted a more soothing call to tell his men that the day was over, so he turned to an old, unused tune called Scott's Tattoo.

The term tattoo was derived from an old Dutch military word which meant it was time to turn off the beer taps and return to camp. Tattoo was usually played about an hour before lights out, to give soldiers time to prepare to end the day.

Scott's Tattoo had been replaced by a newer tattoo in the Union Army, and Butterfield felt it was a good starting place for his new call to lights out. He called for his brigade's bugler, Oliver Wilcox Norton, and the two worked together to write Taps. Here is Norton's account of how that meeting went:

"One day, soon after the seven days’ battles on the Peninsular, when the Army of the Potomac was lying in camp at Harrison’s Landing, General Daniel Butterfield sent for me, and showing me some notes on a staff written in pencil on the back of an envelope, asked me to sound them on my bugle. I did this several times, playing the music as written. He changed it somewhat, lengthening some notes and shortening others, but retaining the melody as he first gave it to me. After getting it to his satisfaction, he directed me to sound that call for “Taps” thereafter in place of the regulation call. The music was beautiful on that still summer night and was heard far beyond the limits of our Brigade. The next day I was visited by several buglers from neighboring brigades, asking for copies of the music which I gladly furnished. I think no general order was issued from army headquarters authorizing the substitution of this for the regulation call, but as each brigade commander exercised his own discretion in such minor matters, the call was gradually taken up through the Army of the Potomac."

As Norton suggested, Taps spread quickly within the Army of the Potomac, and soon saw widespread use as the call to lights out. Within a few months, it had become common to use Taps during funeral services (thanks to Captain Tidball).

The tune also quickly gained widespread use for lights out in the Confederate Armies, and roughly ten months after Butterfield and Norton put the finishing touches on Taps, it was played at the funeral service of Confederate General Stonewall Jackson.

Here is an interesting History Channel video about the history of Taps, and it also includes the famous "broken note" from President John F. Kennedy's funeral...

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.