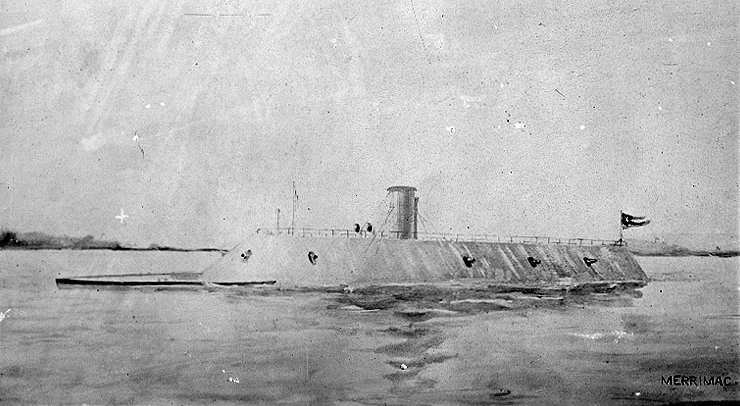

CSS Virginia

The CSS Virginia was the first ironclad built by the Confederate Navy. The CSS Manassas was built before the Virginia, but the Manassas was built by private individuals looking to use the ship as a privateer.

The Virginia's most significant contribution to history was her participation in the momentous Battle of Hampton Roads. This battle, the first in which two ironclad warships (the Virginia and the USS Monitor ) faced off, emphatically marked the end of the age of the wooden battleship. As the Virginia's Chief Engineer H. Ashton Ramsay put it, "...old methods had passed away, and with them the experience of a thousand years 'of battle and of breeze' was brought to naught."

You may be thinking, "Wait! The first battle between ironclads was between the Monitor and the Merrimac."

If you are, you are correct.

...well, sort of.

The Virginia's name has caused quite a bit of confusion over the years, and is still doing so today. Originally, she was the USS Merrimack, a wooden sailing frigate also equipped with steam power. When Union forces abandoned the Norfolk Naval Yards in 1861, they burned the Merrimack to the waterline and then sank her in an attempt to keep the ship from falling into Confederate hands.

...they failed. The Confederate Navy immediately raised the ship and set about converting her into an ironclad. With her conversion, she was renamed the CSS Virginia. Northern newspapers and officials, however, continued to refer to her as the Merrimack both during and after the war.

Somewhere along the line, someone started using the misspelling Merrimac, and it seems to have become at least as popular as either of the actual names the ship had. In fact, in modern day Hampton Roads, Virginia, the Monitor-Merrimac Memorial Bridge-Tunnel bears the misspelled version of the Virginia's old name.

So which name is correct? I don't think it's that big of a deal, but I always use Virginia. Why? Well, mainly because that was the actual name of the ship that took part in the Battle of Hampton Roads; but that's just me...

You may also be wondering how they converted a burned wooden ship into an ironclad. According to Ramsay, it went something like this:

"Her charred upper works were cut away, and in the center a casement shield one hundred and eighty feet long was built of pitch-pine and oak, two feet thick. This was covered with iron plates, one to two inches thick and eight inches wide, bolted over each other and through and through the woodwork, giving a protective armor four inches in thickness. The shield sloped at an angle of about thirty-six degrees, and was covered with an iron grating that served as an upper deck. For fifty feet forward and aft her decks were submerged below the water, and the prow was shod with an iron beak to receive the impact when ramming."

He goes on to note that not everyone was convinced the new-fangled design was a good idea, "...naval officers were skeptical as to the result." The only way to find out how effective the innovative new warship would be was to wait until it was tested in battle...

Into Action

That test would come somewhat sooner than some of the officers in charge fitting her out might have wished. According to Ramsay, there was still a lot of work going on when the CSS Virginia's Captain arrived to take command of his ship:

"The ship was still full of workmen hurrying her to completion when Commodore Franklin Buchanan arrived from Richmond one March morning and ordered every one out of the ship, except her crew of three hundred and fifty men which had been hastily drilled on shore in the management of the big guns, and directed Executive Officer Jones to prepare to sail at once."

The Virginia's Lieutenant, Catesby ap Roger Jones, goes into greater detail when describing the ship's shortcomings when she set sail:

"A trial was determined upon, although the vessel was in an incomplete condition. The lower part of the shield forward was only immersed a few inches, instead of two feet as was intended; and there was but one inch of iron on the hull. The port shutters, etc., were unfinished.

The Virginia was unseaworthy, her engines were unreliable, and her draft, over twenty-two feet, prevented her from going to Washington. Her field of operation was therefore restricted to the bay and its immediate vicinity."

The pressure was on, however, for the Confederate Navy to try to do something about the Union blockade in Hampton Roads. Therefore, on March 8, 1862, the CSS Virginia set off on her first foray against the enemy. This is how Lieutenant Jones described the action that day:

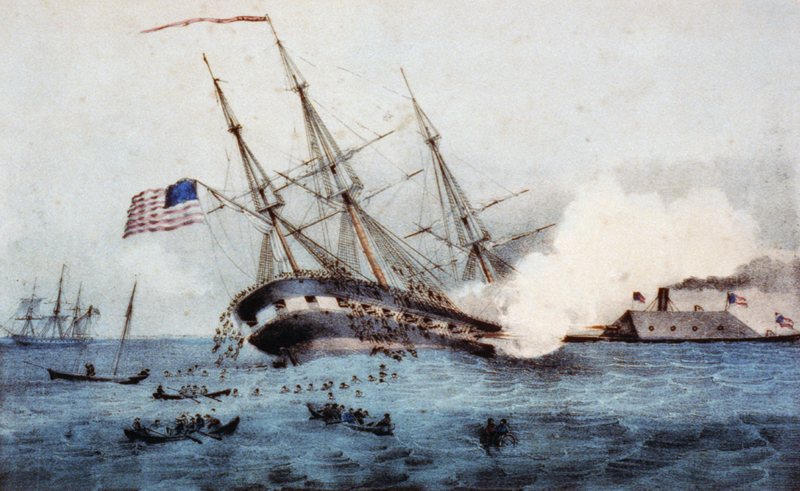

"We left the Navy Yard at 11 A. M., against the last half of the flood tide, steamed down the river past our batteries, through the obstructions, across Hampton Roads, to the mouth of James River, where off Newport News lay at anchor the frigates Cumberland and Congress, protected by strong batteries and gunboats. The action commenced about 3 P. M. by our firing the bow gun at the Cumberland, less than a mile distant. A powerful fire was immediately concentrated upon us from all the batteries afloat and ashore. The frigates Minnesota, Roanoke and St. Lawrence, with other vessels, were seen coming from Old Point. We fired at the Congress on passing, but continued to head directly for the Cumberland, which vessel we had determined to run into, and in less than fifteen minutes from the firing of the first gun we rammed her just forward of the starboard fore-chains. There were heavy spars about her bows, probably to ward off torpedoes, through which we had to break before reaching the side of the ship. The noise of crashing timbers were distinctly heard above the din of battle. There was no sign of the hole above water. It must have been large, as the ship soon commenced to careen. The shock to us on striking was slight. We immediately backed the engines. The blow was not repeated. We here lost the prow, and had the stem slightly twisted. The Cumberland fought her guns gallantly as long as they were above water. She went down bravely, with her colors flying.

...

The action continued until dusk, when we were forced to seek an anchorage. The Congress was riddled and on fire. A transport steamer was blown up. A schooner was sunk and another captured. We had to leave without a serious attack on the Minnesota..."

That night everyone around Hampton Roads watched the Congress burn. It was obvious that wooden ships were no match for the "Rebel Monster," but how would she fare against new ironclads the Union Navy was developing?

No one had to wait long to find out. That very night the first of those Union ironclads, the USS Monitor, slipped into Hampton Roads and took up a position waiting for the return of the Virginia.

The next morning the Virginia returned to the Roads to continue her assault on the Union blockade, and there she found the Monitor. The two ships immediately began to bombard one another, neither gained much of an advantage. Lieutenant Jones relates how the battle finally came to a close:

"The fighting had continued for over three hours. To us the Monitor appeared unharmed. We were therefore surprised to see her run off into shoal water where our great draft would not permit us to follow, and where our shell could not reach her. The loss of our prow and anchor, and consumption of coal, water, etc., had lightened us so that the lower part of the forward shield was awash.

We for some time awaited the return of the Monitor to the Roads. After consultation it was decided that we should proceed to the Navy Yard, in order that the vessel should be brought down into the water and completed. The pilot said that if we did not then leave that we could not pass the bar until noon of the next day. We therefore at 12 M. quit the Roads and stood for Norfolk. Had there been any sign of the Monitor's willingness to renew the contest we would have remained to fight her. We left her in the shoal water to which she had withdrawn, and which she had not left until after we had crossed the bar on our way to Norfolk."

Both sides promptly claimed victory. Looking back, the Battle of Hampton Roads is usually classed as a draw or an inconclusive battle. One thing that wasn't inconclusive, however, was the fact that wooden ships wouldn't survive for long in naval warfare now that machines like the Monitor and the Virginia had arrived on the scene.

The Last Days of the CSS Virginia

After the battle, the Monitor was given strict orders not to engage in battle with the Virginia again. After some repairs and completing her armor, the Virginia made several trips to Hampton Roads in the hopes of facing the Monitor once more. The Monitor, along with the rest of the Union blockade, declined combat every time.

On one occasion, the Virginia and some consorts captured three Union merchant ships right in front of the squadron. They then proceeded to tow their prizes past the squadron and back to Norfolk with the merchant's Union flags flying upside down. Despite all this, the Union squadron steadfastly refused to fight. Because of this, the two legendary ironclads never met again.

On May 10, 1862, Union forces retook Norfolk, and the Virginia lost her port. Chief Engineer Ramsay relates what happened next:

"Norfolk was now being evacuated and we were covering Huger's retreat. When this was effected we were to receive the signal and to make our own way up the James. Norfolk was in Federal hands, and Huger had disappeared without signaling us, when our pilots informed us that Harrison's Bar, which we must cross, drew only eighteen feet of water. Under their advice, on the night of May 11th we lightened ship by throwing overboard all our coal and ballast, thus raising our unprotected decks above water. At last all was ready — and then we found that the wind which had been blowing down-stream all day had swept the water off the bar. When morning dawned the Federal fleet must discover our defenseless condition, and defeat and capture were certain, for we were now no longer an ironclad.

It was decided to abandon the vessel and set her on fire...

Still unconquered, we hauled down our drooping colors, their laurels all fresh and green, with mingled pride and grief, gave her to the flames, and set the lambent fires roaring about the shotted guns. The slow match, the magazine, and that last, deep, low, sullen, mournful boom told our people, now far away on the march, that their gallant ship was no more."

American Civil War Story - Home

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.