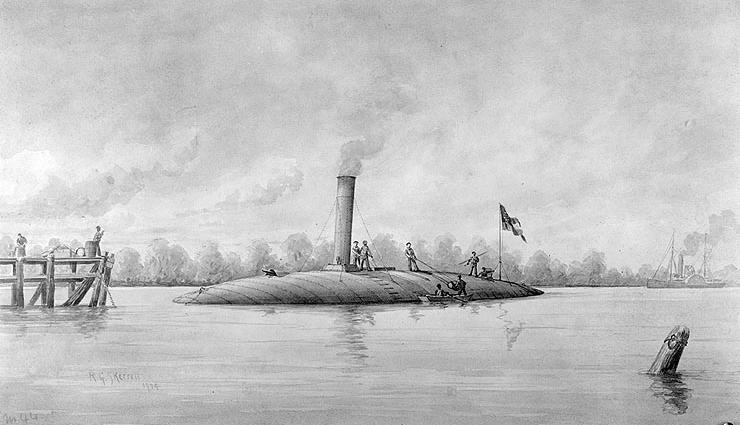

CSS Manassas

The CSS Manassas was the first Confederate ironclad, and had an interesting if short career in the American Civil War...

The Manassas was the brainchild of a southerner by the name of J. J. Peetz. Mr Peetz built a model of his concept and tried to get it built for the defense of Mobile Bay, but he was rebuffed. Finally, his concept was taken and brought to fruition by some men interested in using the ship as a privateer (government sanctioned pirate).

They did not build the Manassas from scratch, instead they took the existing twin screw steam tug Enoch Train and built a protective iron shell over the deck, and added a reinforced iron ram to the prow. Here is Mr. Peetz's description of the refitting of the Enoch Train:

"The boat turned into the ram was reconstructed by putting on an extra bow made solid and extending out a few feet, with an iron prow for ramming purposes. A shield, or roof , was put over the deck in the shape of a turtle back. The frames were eight inches thick, molding way:that is, solid against each other crossways from forward to aft, and the planking on top of this was four inches thick. Outside of this she was covered with a single layer of flat street car iron, such as was used at that time to run the street cars on, not rails such as are used now. On the waterline all around she had a solid sponson four feet thick to protect her from being rammed. She carried two 68-pounders, one over the stem and the other over the stern-post. She had a projecting stem below the water line, extending out two feet, for the purpose of ramming. When the ram was all ready, Capt. Alexander Frazer Warley, a graduate of Annapolis, was placed in command, and I was taken on board as Quartermaster."

I'm not real sure how accurate Peetz's description is, especially concerning the two big guns he says the Manassas was to carry. Here is the Captain Warley's description of the ship, including her armament, at her final battle:

"...the Manassas was ... a tow-boat boarded over with five-inch timber and armored with one thickness of flat railroad iron, with a complement of thirty-four persons and an armament of one light carronade and four double-barreled guns. She was very slow. I do not think she made at any time that night more than five miles an hour."

Whatever the case, the Manassas was a sleek futuristic looking machine in the water. Her curved deck only protruded about five and a half feet above the surface of the water, and provided no good target to her enemy. One Union report described the Manassas as a "hellish machine."

Sounds like a pretty unique - pirate - err, privateer ship, doesn't it? Well, that dream was not meant to be...

Shortly after construction was finished on the Manassas, she was seized by the Confederate Navy and the aforementioned Lieutenant A. F. Warley was made her captain. The ship did not have long to wait before Warley took her into action for the first time...

First Battle-Surprise Attack

On October 12, 1861, the CSS Manassas became the first ironclad to be involved in a naval battle in the Civil War when she took part in a surprise attack in the Battle of the Head of Passes.

The Head of Passes is situated at the mouth of the Mississippi River below New Orleans, and was at that time being blockaded by the Union Navy. In an effort to lift the blockade, the small Confederate river defense fleet, also known as the "mosquito fleet," launched a surprise attack on the blockading Union squadron with the Manassas as the focal point of the attack.

Under cover of darkness, the Manassas slid into the Head of Passes and made for the Union flagship, the USS Richmond, intent on ramming her. As she closed in on her target, the Manasses was spotted, and the Union ships opened fire. Most of the shots completely missed because of her low profile, and those that did hit her simply glanced of the rounded iron shell of the ironclad.

The crew on board the Manassas revved her engines to full speed and rammed the Richmond; but it was not a direct blow, and though damaged, the Richmond was not sunk. One factor that may have saved the Richmond was a coal barge that was tied up alongside the flagship at the time of the attack and may have partially shielded the Richmond from the full force of the ram.

As the Manassas turned from the attack, the rest of the "mosquito fleet" came into the Head of Passes to continue the assault by deploying three fire rafts in the direction of the Union ships. Upon seeing these new dangers, the Union fleet slipped anchors and fled from the Passes.

While the "mosquito fleet" had succeeded in driving away the blockade, they had not been able to sink any of the Union ships during the raid; and the smaller Confederate fleet had withdraw from the Passes leaving them open for the Union fleet to return once they regained their nerve.

While ramming the Richmond, the Manassas had lost her smoke stacks and broken the mounts on one of her engines. These problem sent the ironclad back to the docks for repairs. When she was repaired, she was sent to help hold the river below New Orleans at Forts Jackson and St. Phillip. Here is where the innovative ship would make her final stand...

Last Battle-A Watery Grave

Forts Jackson and St. Phillip were situated on opposite sides of the Mississippi River between Head of Passes and New Orleans. In order to take New Orleans, the Union Navy needed to be able to get by these two forts and their 177 guns which bore on the river.

Knowing this, the Manassas, along with the rest of the "mosquito fleet," were stationed near the forts to try to help hold back the expected Union attack. It was well known that if the Union Navy could get past the forts, there was no other defense for New Orleans, and the largest city in the Confederacy would be doomed.

On the the morning of April 24, 1862, the Union fleet began passing the forts, and the CSS Manassas engaged some ships in the fleet and tried to impede their progress. Here is Captain Warley's account of the Battle of Forts Jackson and St. Philip:

"The Manassas was made fast to the bank on the Fort St. Philip side above the forts, and had alongside of her a heavy steam-tug to enable her to be turned promptly down the river. On the evening before the attack I went on board of the Confederate steamer McRae, carrying some letters to put in the hands of my friend Captain Huger, and found him just starting to call on me, on the same errand. Both of us--judging from the character of the officers in the enemy's fleet, most of whom we knew - believed the attack was at hand, and neither of us expected support from the vessels that had been sent down to help oppose the fleet.

Before night all necessary orders had been given, and when at 3:30 A. M. the dash of the first gun was seen on the river below the forts, the Manassas was cut away from the bank, turned downstream, cast off from the tug, and was steaming down to the fleet in quicker time than I had believed to be possible.

The first vessel seen was one of the armed Confederate steamers. She dashed up the river, passing only a few feet from me, and no notice was taken of my hail and request for her to join me. The next vessel that loomed up was the United States steamer Mississippi. She was slanting across the river when the Manassas was run into her starboard quarter, our little gun being fired at short range through her cabin or ward-room. What injury she received must be told by her people. She fired over the Manassas, tore away, and went into the dark. While this was going on other vessels no doubt passed up, but the first I saw was a large ship (since known to have been the Pensacola). As the Manassas dashed at her quarter, she shifted her helm, avoided the collision beautifully, and fired her stern pivot-gun close into our faces, cutting away the flagstaff.

By that time the Manassas was getting between the forts, and I told Captain Levin, the pilot, that we could do nothing with the vessels which had passed, but we could go down to the mortar-fleet; but no sooner had we got in seeing range than both forts opened on us, Fort Jackson striking the vessel several times on the bend with the lighter guns. I knew the vessel must be sunk if once under the 10-inch guns, so I turned up the river again, and very soon saw a large ship, the Hartford [Brooklyn], lying across-stream. As I was not fired upon by her I thought then that her crew were busy fending off what I think now to have been a, burning pile-driver, and could not see the Manassas coming out of the dark. The Manassas was driven at her with everything open, resin being piled into the furnaces. The gun was discharged when close on board. We struck her fairly amidships; the gun recoiled and turned over and remained there, the boiler started, slightly jamming the Chief Engineer, Dearning, but settled back as the vessel backed off. For any damage done to the Hartford [Brooklyn] her records must be consulted. Just then another steamer came up through the fog. I thought her the Iroquois, and tried to run into her, but she passed as if the Manassas had been at anchor.

Steaming slowly up the river,--very slow was our best,--we discovered the Confederate States steamer McRae, head upstream, receiving the fire of three men-of-war. As the Manassas forged by, the three men-of-war steamed up the river, and were followed to allow the McRae to turn and get down to the forts, as she was very badly used up.

Day was getting broader, and with the first ray of the sun we saw the fleet above us; and a splendid sight it was, or rather would have been under other circumstances. Signals were being rapidly exchanged, and two men-of-war steamed down, one on either side of the river. The Manassas was helpless. She had nothing to fight with, and no speed to run with. I ordered her to be run into the bank on the Fort St. Philip side, her delivery-pipes to be cut, and the crew to be sent into the swamp through the elongated port forward, through which the gun had been used. The first officer, gallant Frank Harris, reported all the men on shore. We examined the vessel, found all orders had been obeyed, and we also took to the swamp.

I think our two attendants ran into each other. Harris said such was the case. At any rate I soon heard heavy firing,--some for our benefit, but most, I think, for the abandoned Manassas. I heard afterward that she was boarded, but, filling astern, floated off, on fire, and blew up somewhere below in the neighborhood of the mortar-fleet.

If on that occasion she was made to do less than she should have done, if she omitted any possible chance of putting greater obstructions in the track of the fleet, the fault was mine,-- for I was trammeled by no orders from superior authority; I labored under no difficulty of divided counsel; I had not to guard against possible disaffection or be jealous about obedience to my orders."

Thus ended the career of the CSS Manassas, the first ironclad of the Confederacy. New Orleans was laid bare, and the city fell just a few days later...

American Civil War Story - Home

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.