Battle of Shiloh

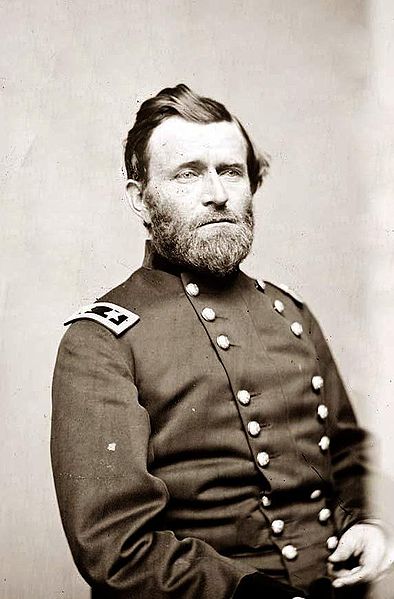

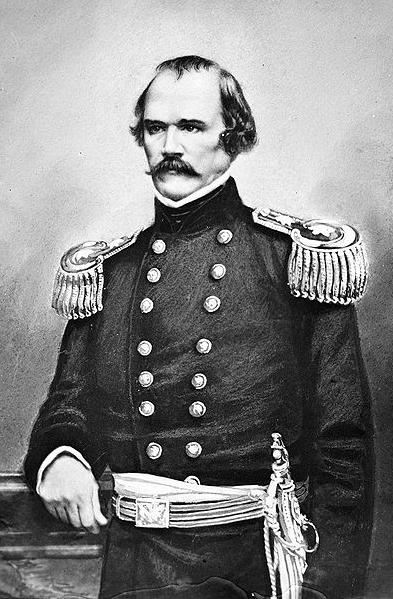

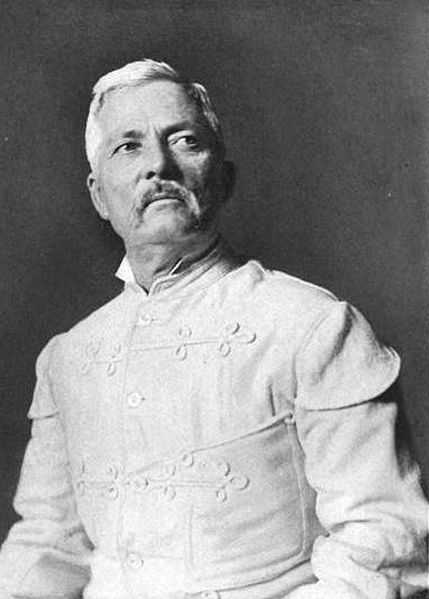

The Battle of Shiloh, also known as the Battle of Pittsburg Landing, took place on April 6-7, 1862. In command of the Union forces was General Ulysses S. Grant (left), and in command of the Confederate forces was General Albert Sidney Johnston (right).

Without a doubt, the Battle of Shiloh is one of the most well-known and much discussed battles of the American Civil War. For this reason, you have probably at least heard the general story of this battle. In case you need a quick refresher of the overall story, here is what happened in a nutshell.

Grant was bringing troops up the Tennessee River and massing them in southern Tennessee in preparation for a strike into Mississippi. In response, Johnston massed a force in nearby Corinth, Mississippi, to oppose him. Johnston decided to attack Grants position in an effort to take him by surprise.

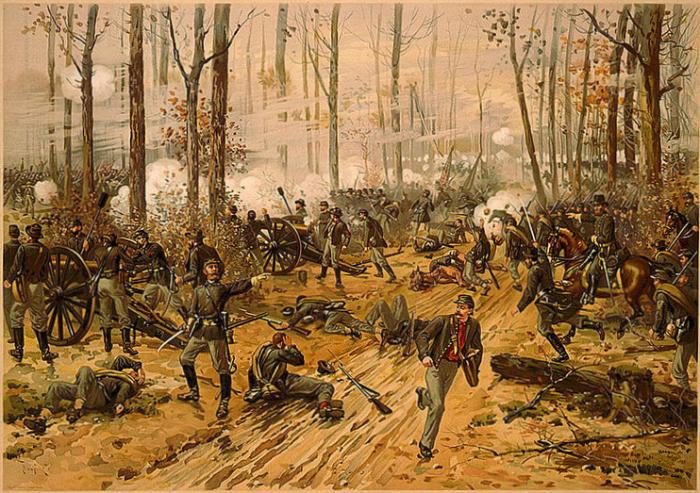

The surprise attack worked fairly well, and the Confederates were able to drive the Union troops back for most of the first day. Johnston was killed during the fight that afternoon. It looked as if the Confederates might be able to crush the Union forces against the Tennessee River, but by evening Grant was able to form a strong defensive line.

During the night General Don Carlos Buell arrived with 20,000 men to reenforce Grant. The next day the fighting continued, but now it favored Grant and his men. Eventually, the Confederate troops under their new commander P. G. T. Beauregard were forced to retreat.

The Battle of Shiloh was the first of the truly bloody battles of the Civil War, with well over 20,000 casualties on both sides. This Union victory finally put to rest the persistent belief, on both sides, that the War would be a quick and exciting adventure.

If you want a better summary of the Battle of Shiloh, you can get a good idea of what went on with this animated history of the battle.

Instead of trying to give you a rundown of the battle, I thought it would be cool to hear about it from the ones who fought it...

Below, I have included excerpts from two accounts of the Battle of Shiloh. These accounts were written by men who served as privates in the two armies that contested this battle.

I give a brief introduction for each account, and where parts of the account have been left out for the sake of brevity it is indicated by dashes (---). Please enjoy these 'stories,' as told by the men who lived them.

Also, check out this amazing story of wounded men at the Battle of Shiloh whose wounds glowed in the dark and, as a result, healed better and more quickly than normal.

A Yankee account...

For a Yankee account of the Battle of Shiloh, we will hear from Warren Olney. Mr. Olney was a private in the 3rd Iowa Infantry at the time of the battle, and the following is a portion of his recollections of the Battle of Shiloh...

"A sense of apprehension took possession of me. Presently artillery was heard, and then I turned toward camp, getting more alarmed at every step. When I reached camp a startled look was on every countenance. The musketry firing had become loud and general, and whole batteries of artillery were joining in the dreadful chorus. The men rushed to their tents and seized their guns, but as yet no order to fall in was given. Nearer and nearer sounded the din of a tremendous conflict. Presently the long roll was heard from the regiments on our right. A staff officer came galloping up, spoke a word to the Major in command, the order to fall in was shouted, the drummers began to beat the long roll, and it was taken up by the regiments on our left. The men, with pale faces, wild eyes, compressed lips, quickly accoutered themselves for battle. The shouts of the officers, the rolling of the drums, the hurrying to and fro of the men, the uproar of approaching but unexpected battle, all together produced sensations which cannot be described. Soon, teams with shouting drivers came tearing along the road toward the landing. Crowds of fugitives and men slightly wounded went hurrying past in the same direction. Uproar and turmoil were all around; but we, having got into line, stood quietly with scarcely a word spoken.

Presently a staff officer rode up, the command to march was given, and with the movement came some relief to the mental and moral strain. As we passed in front of the Forty-first Illinois, a field officer of that regiment, in a clear, ringing voice, was speaking to his men, and announced that if any man left the ranks on pretense of caring for the wounded he should be shot on the spot; that the wounded must be left till the fight was over. His men cheered him, and we took up the cheer. Blood was beginning to flow through our veins again, and we could even comment to one another upon the sneaks who remained in camp, on pretense of being sick. As we moved toward the front the fugitives and the wounded increased in numbers. Poor wretches, horribly mutilated, would drop down, unable to go farther. Wagons full of wounded, filling the air with their groans, went hurrying by. As we approached the scene of conflict, we moved off to the left of the line of the rear-ward going crowd, crossed a small field and halted in the open woods beyond. As we halted, we saw right in front of us, but about three hundred or four hundred yards off, a dense line of Confederate infantry, quietly standing in ranks. In our excitement, and without a word of command, we turned loose and with our smooth bore muskets opened fire upon them. After three or four rounds, the absurdity of firing at the enemy at that distance with our guns dawned upon us, and we stopped. As the smoke cleared up we saw the enemy still there, not having budged or fired a shot in return. But though our action was absurd, it was a relief to us to do something, and we were rapidly becoming toned up to the point of steady endurance.

As we gazed at the enemy so coolly standing there, an Ohio battery of artillery came galloping up in our rear, and what followed I don't believe was equalled by anything of the kind during the war. As the artillery came up we moved off by the right flank a few steps, to let it come in between us and the Illinois regiment next on our left. Where we were standing was in open, low-limbed oak timber. The line of Southern infantry was in tolerably plain view through the openings in the woods, and were still standing quietly. Of course, we all turned our heads away from them to look at the finely equipped battery, as it came galloping from the rear to our left flank, its officers shouting directions to the riders where to stop their guns. It was the work of but an instant to bring every gun into position. Like a flash the gunners leaped from their seats and unlimbered the cannon. The fine six-horse teams began turning round with the caissons, charges were being rammed home, and the guns pointed toward the dense ranks of the enemy, when, from right in front, a dense puff of smoke, a tearing of shot and shell through the trees, a roar from half a dozen cannon, hitherto unseen, and our brave battery was knocked into smithereens. Great limbs of trees, torn off by cannon shot, came down on horse and rider, crushing them to earth. Shot and shell struck cannon, upsetting them; caissons exploded them. Not a shot was fired from our side.

---

This made us feel mightily uncomfortable—in fact, we had been feeling quite uncomfortable all the morning. It did not particularly add to the cheerfulness of the prospect, to reflect that our division was the reserve of the army, and should not be called into action, ordinarily, until towards the close of the battle; while here we were, early in the forenoon, face to face with the enemy, our battery of artillery gobbled up at one mouthful, and the rest of the army in great strait, certainly, and probably demoralized.

---

... another battery came up and opened on the enemy, who had moved up almost to the wreck of our first battery.

Here, then, began a fierce artillery duel. Shot and shell went over us and crashing through the trees to the rear of us, and I suppose that shot and shell went crashing through the trees above the enemy; but if they didn't suffer any more from shot and shell than we did, there was a great waste of powder and iron that day. But how a fellow does hug the ground under such circumstances! As a shell goes whistling over him he flattens out, and presses himself into the earth, almost. Pity the sorrows of a big fat man under such a fire.

---

Two or three times General Hurlbut came riding along our line; and once, during a lull, General Grant and staff came slowly riding by, the General with a cigar in his mouth, and apparently as cool and unconcerned as if inspection was the sole purpose of visiting us. The General's apparent indifference had, undoubtedly, a good influence on the men. They saw him undisturbed, and felt assured that the worst was over, and the attack had spent its force. This must have been soon after he reached the field; for, upon hearing the roar of battle in the morning at Savannah he went aboard a steamer, came up the river eight or nine miles, and did not reach the scene of action much, if any, before 10 o'clock. By that time, Sherman, McClernand and Prentiss had been driven more than a mile beyond their camps, and with such of their command as they could hold together had formed on the flanks of the two reserve divisions of Hurlbut and W. H. L. Wallace, who had moved forward beyond their own camps to meet them.

---

As for myself and comrades, we had become accustomed to the situation somewhat. The lull in the fighting in our immediate vicinity, and the reports which reached us that matters were now progressing favorably on the rest of the field, reassured us. We were becoming quite easy in mind. I had always made it a rule to keep a supply of sugar and some hard tack in my haversack, ready for an emergency. It stood me in good stead just then, for I alone had something besides fighting for lunch. I nibbled my hard tack, and ate my sugar with comfort and satisfaction, for I don't believe three men of our regiment were hurt by this artillery fire upon us, which had been kept up with more or less fury for two or three hours.

One of the little episodes of the battle happened about this time. We noticed that a Confederate, seated on one of the abandoned cannon I have mentioned, was leisurely taking an observation. He was out of range of our guns, but our First Lieutenant got a rifle from a man who happened to have one, took deliberate aim, and Johnny Reb tumbled.

But soon after noon the Confederate forces were ready to hurl themselves on our lines. There had been more or less fighting on our right all the time, but now Johnston had collected his troops and massed them in front of the Union army's left. Language is inadequate to give an idea of the situation. Cannon and musketry roared and rattled, not in volleys, but in one continual din. Charge after charge was made upon the Union lines, and every time repulsed.

---

The left wing of our brigade was the Hornet's Nest, mentioned in the Southern accounts of the battle. On the immediate right of my regiment was timber with growth of underbrush, and the dreadful conflict set the woods on fire, burning the dead and the wounded who could not crawl away. At one point not burned over, I noticed, after the battle, a strip of low underbrush which had evidently been the scene of a most desperate contest. Large patches of brush had been cut off by bullets at about as high as a man's waist, as if mowed with a scythe, and I could not find in the whole thicket a bush which had not at some part of it been touched by a ball. Of course, human beings could not exist in such a scene, save by closely hugging the ground, or screening themselves behind trees.

Hour after hour passed. Time and again the Confederate hordes threw themselves on our lines, and were repulsed; but our ranks were becoming dangerously thinned. If a few thousand troops could have been brought from Lew Wallace's division to our sorely-tried left the battle would have been won. His failure to reach us was fatal.

Yet, during all this terrible ordeal through which our comrades on the immediate right and the left of us were passing, we were left undisturbed until about two o'clock. Then there came from the woods on the other side of the field, to the edge of it, and then came trotting across it, as fine looking a body of men as I ever expect to see under arms. They came with their guns at what soldiers call right shoulder shift. Lying on the ground there, with the rails of the fence thrown down in front of us, we beheld them, as they started in beautiful line; then increasing their speed as they neared our side of the field, they came on till they reached the range of our smooth bore guns, loaded with buck and ball. Then we rose with a volley right in their faces. Of course, the smoke then entirely obscured the vision, but with eager, bloodthirsty energy, we loaded and fired our muskets at the top of our speed, aiming low, until, from not noticing any return fire, the word passed along from man to man to stop firing. As the smoke rose so that we could see over the field, that splendid body of men presented to my eyes more the appearance of a wind-row of hay than anything else. They seemed to be piled up on each other in a long row across the field. Probably the obscurity caused by the smoke, as well as the slight slope of the ground towards us, accounted for this piled up appearance, for it was something which could not possibly occur. But the slaughter had been fearful. Here and there you could see a squad of men running off out of range; now and then a man lying down, probably wounded or stunned, would rise and try to run, soon to tumble from the shots we sent after him.

---

The Confederates had all they wanted of charging across the field, and let us alone. But just to our left General Johnston had personally organized and started a heavy assaulting column. Overwhelmed by numbers, the Forty-first and Thirty-second Illinois gave way from the position they had so tenaciously held, but one of their last shots mortally wounded the Confederate general. The gallant Lieutenant-Colonel of the Forty-first, whom we had cheered as we moved out in the morning, was killed, and his regiment, broken and cut to pieces, did not renew the fight. Making that break in our line, after four or five hours of as hard fighting as ever occurred on this continent, was the turning point of the day. American had met American in fair, stand-up fight, and our side was beaten, because we could not reinforce the point which was assailed by the concentrated forces of the enemy.

Of course, the giving way on our left necessitated our abandoning the side of the field from whence we had annihilated an assaulting column. We moved back a short distance in the woods, and a crowd of our enemies promptly occupied the position we had left. Then began the first real, prolonged fighting experienced by our regiment that day. Our success in crushing the first attack had exhilarated us. We had tasted blood and were thoroughly aroused. Screening ourselves behind every log and tree, all broken into squads, the enemy broken up likewise, we gave back shot for shot and yell for yell. The very madness of bloodthirstiness possessed us. To kill, to exterminate the beings in front of us was our whole desire. Such energy and force was too much for our enemies, and ere long we saw squads of them rising from the ground and running away. Again there was no foe in our front. Ammunition was getting short, but happily a wagon came up with cartridges, and we took advantage of the lull to fill our boxes. We had not yet lost many men and were full of fight.

---

Unless in making an assault or moving forward, both sides hugged the ground as closely as they possibly could and still handle their guns. I doubt if a human being could have existed three minutes, if standing erect in open ground under such a fire as we here experienced. As for myself, at the beginning I jumped behind a little sapling not more than six inches in diameter, and instantly about six men ranged themselves behind me, one behind the other. I thought they would certainly shoot my ears off, and I would be in luck if the side of my head didn't go. The reports of their guns were deafening. A savage remonstrance was unheeded. I was behind a sapling and proposed to stay there. They were behind me and proposed to stay there.

The sapling did me a good turn, small as it was. It caught some Rebel bullets, as I ascertained for a certainty afterwards. I fancied at the time that I heard the spat of the bullets as they struck.

Here my particular chum was wounded by a spent ball, and crawled off the field. I can see him yet, writhing at my feet, grasping the leaves and sticks in the horrible pain which the blow from a spent ball inflicts. A bullet struck the top of the forehead of the wit of the company, plowing along the skull without breaking it. His dazed expression, as he turned instinctively to crawl to the rear, was so comical as to cause a laugh even there.

---

Then began another fight. But this time the odds were overwhelmingly against us. At it we went, but in front and quartering on the left thick masses of the enemy slowly but steadily advanced upon us. This time it was a log I got behind, kneeling, loading and firing into the dense ranks of the enemy advancing right in front, eager to kill, kill! I lost thought of companions, until a ball struck me fair in the side, just under the arm, knocking me over. I felt it go clear through my body, struggled on the ground with the effect of the blow for an instant, recovered myself, sprang to my feet, saw I was alone, my comrades already on the run, the enemy close in on the left as well as front—saw it all at a glance, felt I was mortally wounded, and—took to my heels. Run! such time was never made before; overhauled my companions in no time; passed them; began to wonder that a man shot through the body could run so fast, and to suspect that perhaps I was not mortally wounded after all; felt for the hole the ball had made, found it in the blouse and shirt, bad bruise on the ribs, nothing more—spent ball; never relaxed my speed; saw everything around—see it yet. I see the enemy close in on the flank, pouring in their fire at short range. I see our men running for their lives, men every instant tumbling forward limp on their faces, men falling wounded and rolling on the ground, the falling bullets raising little puffs of dust on apparently every foot of ground, a bullet through my hair, a bullet through my trousers. I hear the cruel iz, iz, of the minie balls everywhere. Ahead I see artillery galloping for the landing, and crowds of men running with almost equal speed, and all in the same direction. I even see the purple tinge given by the setting sun to the dust and smoke of battle. I see unutterable defeat, the success of the rebellion, a great catastrophe, a moral and physical cataclysm.

No doubt, in less time than it takes to recall these impressions, we ran out of this horrible gauntlet—a party who shall be nameless still in the lead of the regiment.

Before getting out of it we crossed our camp ground, and here one of our college set, the captain of the company fell, with several holes through his body, while two others of our set were wounded. In that short race at least one-third of our little command were stricken down.

Immediately behind us the Confederates closed in, and the brave General Prentiss and the gallant remains of his command were cut off and surrendered. As we passed out of range of the enemy's fire we mingled with the masses of troops skurrying towards the landing, all semblance of organization lost. It was a great crowd of beaten troops. Pell-mell we rushed towards the landing. As we approached it we saw a row of siege guns, manned and ready for action, while a dense mass of unorganized infantry were rallied to their support. No doubt they were men from every regiment on the field, rallied by brave officers for the last and final stand.

We passed them—or, at least, I did. As I reached the top of the bluff I saw, marching up, in well dressed lines, the advance of General Nelson's division of Buell's army, then being ferried across the river. They moved up the bluff and took part in repulsing the last, rather feeble assault made at dark by a small portion of the enemy, though the main defense was made by brave men collected from every quarter of the field, determined to fight to the last.

As for myself, I was alone in the crowd. My regiment was thoroughly scattered. I was considerably hurt and demoralized, and didn't take a hand in the last repulse of the enemy. Darkness came on, and then, for the first time since morning, the horrid din of fire-arms ceased. An examination showed that the ball, though it had hit me fair on the rib, was so far spent that it only made a bad bruise and respiration painful. A requisition on the sugar and hard tack followed, and then, as I happened to be near an old house filled with wounded, most of the night was spent in carrying them water.

The next morning the contest was begun by Wallace's division of Buell's army. The remnants of Grant's army that had any fight left in them, slowly collected together on the right.

My own regiment, when I found its colors, had as many men together, probably, as any in Hurlbut's division, but there could not have been more than one hundred and fifty. It was the same, I suspect, with every regiment that had been hotly engaged. The men were thoroughly scattered. Soldiers of pluck joined us who could not find their own command, and no doubt some of ours joined other regiments.

When our general was again about to lead our division to the front, I was only too glad to avail myself of permission to join a body of men to support a battery in reserve. Badly bruised, sore and worn out, I sat or lay on the ground near the guns, while Monday's battle progressed, the sound of it getting farther and farther away. About two o'clock we saw the cavalry moving to the front, and knew the enemy had retreated."

A Rebel Account...

For our Rebel account from the Battle of Shiloh, we will hear from none other than the famed Welsh explorer Henry M. Stanley. The same man that went into the interior of Africa to find Dr. David Livingstone once served as a private in the 6th Arkansas infantry. Here is part of Stanley's account of the Battle of Shiloh, in which he was captured...

"As we tramped solemnly and silently through the thin forest, and over its grass, still in its withered and wintry hue, I noticed that the sun was not far from appearing, that our regiment was keeping its formation admirably, that the woods would have been a grand place for a picnic; and I thought it strange that a Sunday should have been chosen to disturb the holy calm of those woods.

Before we had gone five hundred paces, our serenity was disturbed by some desultory firing in front. It was then a quarter-past five. 'They are at it already,' we whispered to each other. 'Stand by, gentlemen,' — for we were all gentlemen volunteers at this time, — said our Captain, L. G. Smith.

Our steps became unconsciously brisker, and alertness was noticeable in everybody. The firing continued at intervals, deliberate and scattered, as at target-practice. We drew nearer to the firing, and soon a sharper rattling of musketry was heard. 'That is the enemy waking up,' we said. Within a few minutes, there was another explosive burst of musketry, the air was pierced by many missiles, which hummed and pinged sharply by our ears, pattered through the tree-tops, and brought twigs and leaves down on us.

At two hundred yards further, a dreadful roar of musketry broke out from a regiment adjoining ours. It was followed by another further off, and the sound had scarcely died away when regiment after regiment blazed away and made a continuous roll of sound.

'Forward, gentlemen, make ready!' urged Captain Smith. In response, we surged forward...

---

Just then we came to a bit of packland, and overtook our skirmishers, who had been engaged in exploring our front. We passed beyond them. Nothing now stood between us and the enemy.

'There they are!' was no sooner uttered, than we cracked into them with leveled muskets. 'Aim low, men!' commanded Captain Smith. I tried hard to see some living thing to shoot at, for it appeared absurd to be blazing away at shadows. But, still advancing, firing as we moved, I, at last, saw a row of little globes of pearly smoke streaked with crimson, breaking out, with spurtive quickness, from a long line of bluey figures in front; and, simultaneously, there broke upon our ears an appalling crash of sound, the series of fusillades following one another with startling suddenness, which suggested to my somewhat moidered sense a mountain upheaved, with huge rocks tumbling and thundering down a slope, and the echoes rumbling and receding through space. Again and again, these loud and quick explosions were repeated, seemingly with increased violence, until they rose to the highest pitch of fury, and in unbroken continuity. All the world seemed involved in one tremendous ruin!

---

We continued advancing, step by step, loading and firing as we went. To every forward step, they took a backward move, loading and firing as they slowly withdrew. Twenty thousand muskets were being fired at this stage, but, though accuracy of aim was impossible, owing to our labouring hearts, and the jarring and excitement, many bullets found their destined billets on both sides.

After a steady exchange of musketry, which lasted some time, we heard the order: 'Fix Bayonets! On the doublequick,' in tones that thrilled us. There was a simultaneous bound forward, each soul doing his best for the emergency. The Federals appeared inclined to await us; but, at this juncture, our men raised a yell, thousands responded to it, and burst out into the wildest yelling it has ever been my lot to hear. It drove all sanity and order from among us. It served the double purpose of relieving pent-up feelings, and transmitting encouragement along the attacking line. I rejoiced in the shouting like the rest. It reminded me that there were about four hundred companies like the Dixie Greys, who shared our feelings. Most of us, engrossed with the musketwork, had forgotten the fact; but the wave after wave of human voices, louder than all other battle-sounds together, penetrated to every sense, and stimulated our energies to the utmost.

'They fly!' was echoed from lip to lip. It accelerated our pace, and filled us with a noble rage. Then I knew what the Berserker passion was! It deluged us with rapture, and transfigured each Southerner into an exulting victor. At such a moment, nothing could have halted us.

Those savage yells, and the sight of thousands of racing figures coming towards them, discomfited the blue-coats; and when we arrived upon the place where they had stood, they had vanished. Then we caught sight of their beautiful array of tents, before which they had made their stand, after being roused from their Sunday-morning sleep, and huddled into line, at hearing their pickets challenge our skirmishers. The half-dressed dead and wounded showed what a surprise our attack had been. We drew up in the enemy's camp, panting and breathing hard. Some precious minutes were thus lost in recovering our breaths, indulging our curiosity, and re-forming our line.

---

Meantime, a series of other camps lay behind the first array of tents. The resistance we had met, though comparatively brief, enabled the brigades in rear of the advance camp to recover from the shock of the surprise; but our delay had not been long enough to give them time to form in proper order of battle. There were wide gaps between their divisions, into which the quick-flowing tide of elated Southerners entered, and compelled them to fall back lest they should be surrounded. Prentiss's brigade, despite their most desperate efforts, were thus hemmed in on all sides, and were made prisoners.

---

Continuing our advance, we came in view of the tops of another mass of white tents, and, almost at the same time, were met by a furious storm of bullets, poured on us from a long line of blue-coats, whose attitude of assurance proved to us that we should have tough work here. But we were so much heartened by our first success that it would have required a good deal to have halted our advance for long. Their opportunity for making a full impression on us came with terrific suddenness. The world seemed bursting into fragments. Cannon and musket, shell and bullet, lent their several intensities to the distracting uproar. If I had not a fraction of an ear, and an eye inclined towards my Captain and Company, I had been spell-bound by the energies now opposed to us. I likened the cannon, with their deep bass, to the roaring of a great herd of lions; the ripping, cracking musketry, to the incessant yapping of terriers; the windy whisk of shells, and zipping of minie bullets, to the swoop of eagles, and the buzz of angry wasps. All the opposing armies of Grey and Blue fiercely blazed at each other.

---

Our progress was not so continuously rapid as we desired, for the blues were obdurate; but at this moment we were gladdened at the sight of a battery galloping to our assistance. It was time for the nerve-shaking cannon to speak. After two rounds of shell and canister, we felt the pressure on us slightly relaxed; but we were still somewhat sluggish in disposition, though the officers' voices rang out imperiously. Newton Story at this juncture strode forward rapidly with the Dixies' banner, until he was quite sixty yards ahead of the foremost. Finding himself alone, he halted; and turning to us smilingly, said, 'Why don't you come on, boys?' You see there is no danger!' His smile and words acted on us like magic. We raised the yell, and sprang lightly and hopefully towards him. 'Let's give them hell, boys!' said one. 'Plug them plum-centre, every time!'

It was all very encouraging, for the yelling and shouting were taken up by thousands. "Forward, forward; don't give them breathing time!' was cried. We instinctively obeyed, and soon came in clear view of the blue-coats, who were scornfully unconcerned at first; but, seeing the leaping tide of men coming on at a tremendous pace, their front dissolved, and they fled in double-quick retreat. Again we felt the 'glorious joy of heroes.' It carried us on exultantly, rejoicing in the spirit which recognises nothing but the prey. We were no longer an army of soldiers, but so many school-boys racing, in which length of legs, wind, and condition tell.

---

The desperate character of this day's battle was now brought home to my mind in all its awful reality. While in the tumultuous advance, and occupied with a myriad of exciting incidents, it was only at brief intervals that I was conscious of wounds being given and received; but now, in the trail of pursuers and pursued, the ghastly relics appalled every sense. I felt curious as to who the fallen Greys were, and moved to one stretched straight out. It was the body of a stout English Sergeant [from] a neighbouring company, the members of which hailed principally from the Washita Valley. At the crossing of the Arkansas River this plump, ruddy-faced man had been conspicuous for his complexion, jovial features, and goodhumour, and had been nicknamed 'John Bull.' He was now lifeless, and lay with his eyes wide open, regardless of the scorching sun, and the tempestuous cannonade which sounded through the forest, and the musketry that crackled incessantly along the front.

Close by him was a young Lieutenant, who, judging by the new gloss on his uniform, must have been some father's darling. A clean bullet-hole through the centre of his forehead had instantly ended his career. A little further were some twenty bodies, lying in various postures, each by its own pool of viscous blood, which emitted a peculiar scent, which was new to me, but which I have since learned is inseparable from a battle-field. Beyond these, a still larger group lay, body overlying body, knees crooked, arms erect, or wide-stretched and rigid, according as the last spasm overtook them. The company opposed to them must have shot straight.

---

Finally, about five o'clock, we assaulted and captured a large camp; after driving the enemy well away from it, the front line was as thin as that of a skirmishing body, and we were ordered to retire to the tents.

---

Night soon fell, and only a few stray shots could now be heard, to remind us of the thrilling and horrid din of the day, excepting the huge bombs from the gun-boats, which, as we were not far from the blue-coats, discomforted only those in the rear. By eight o'clock, I was repeating my experiences in the region of dreams, indifferent to columbiads and mortars, and the torrential rain which, at midnight, increased the miseries of the wounded and tentless.

---

At daylight, I fell in with my Company, but there were only about fifty of the Dixies present. Almost immediately after, symptoms of the coming battle were manifest. Regiments were hurried into line, but, even to my inexperienced eyes, the troops were in ill-condition for repeating the efforts of Sunday. However, in brief time, in consequence of our pickets being driven in on us, we were moved forward in skirmishing order.

---

I became so absorbed with some blue figures in front of me, that I did not pay sufficient heed to my companion greys; the open space was. too dangerous, perhaps, for their advance; for, had they emerged, I should have known they were pressing forward. Seeing my blues in about the same proportion, I assumed that the greys were keeping their position, and never once thought of retreat. However, as, despite our firing, the blues were coming uncomfortably near, I rose from my hollow; but, to my speechless amazement, I found myself a solitary grey, in a line of blue skirmishers! My companions had retreated! The next I heard was, 'Down with that gun, Secesh, or I'll drill a hole through you! Drop it, quick!'

Half a dozen of the enemy were covering me at the same instant, and I dropped my weapon, incontinently. Two men sprang at my collar, and marched me, unresisting, into the ranks of the terrible Yankees. I was a prisoner!"

Shiloh

This is definitely not a definitive account of the Battle of Shiloh, but I think it is very interesting to see the battle through the eyes of those who fought it. We are able to experience their excitement, fear, exultation, and horror, even a century and a half later. I hope you have enjoyed these stories as much as I did.

New! Comments

Have your say about what you just read! Leave me a comment in the box below.